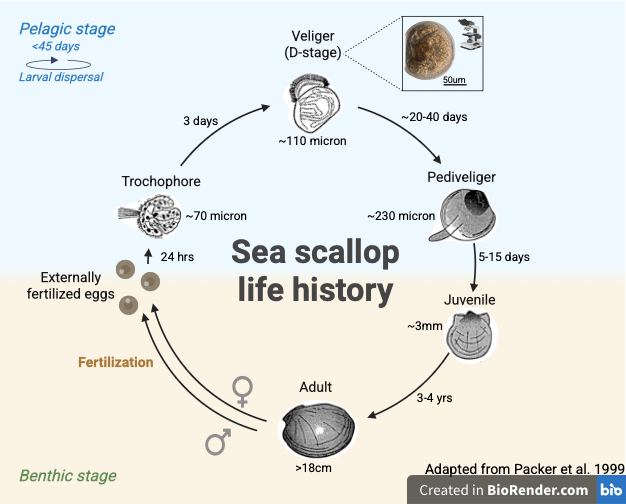

during which the animals are transported by ocean currents,

and a benthic stage in which the scallops live in sandy sediments.

My current research at Stony Brook University is on the effects of ocean acidification and ocean warming on the larval stages of sea scallop and surfclam larvae. The pelagic larval stage is key to understanding the distribution and abundance of shellfish populations. Here I used lab experiments to study the sensitivity of growth and behavior to ocean conditions of both species at the Downeast Institute in Beals, ME. The next step is to use a larval individual based model integrated with a hydrographic model (ROMS) to project change in their dispersal.

At NOAA Fisheries I studied the susceptibility of Atlantic surfclam (Spisula solidissima) to ocean acidification in New England, USA. Ocean acidification is known as the “other CO2 problem” where excess CO2 in the atmosphere from burning fossil fuels dissolves into seawater and causes the pH of the seawater to drop. Previous lab experiments have shown that ocean acidification conditions lower feeding rates and stunt the growth of these clams, but the effect of ocean chemistry on surfclams at the sediment-water interface is not well understood. We were interested in growth in natural sandy shore environments, and the effect of fluctuating ocean chemistry and other factors in and above the sediment on individuals. This project combined a lab-based model of surfclam growth with field measurements to evaluate whether these predictions match actual patterns of growth. Check out our blog.

As a postdoctoral researcher at Claremont McKenna College with Dr. Sarah Gilman, I worked on developing a lab-based model of barnacle growth. We then tested to see if the predictions from the model matched actual growth of barnacles measured at different shore heights. Our simulations showed that while low tide warming was detrimental to their growth, warming water counteracted this negative effect (Roberts et al. 2025 PLOS Climate).

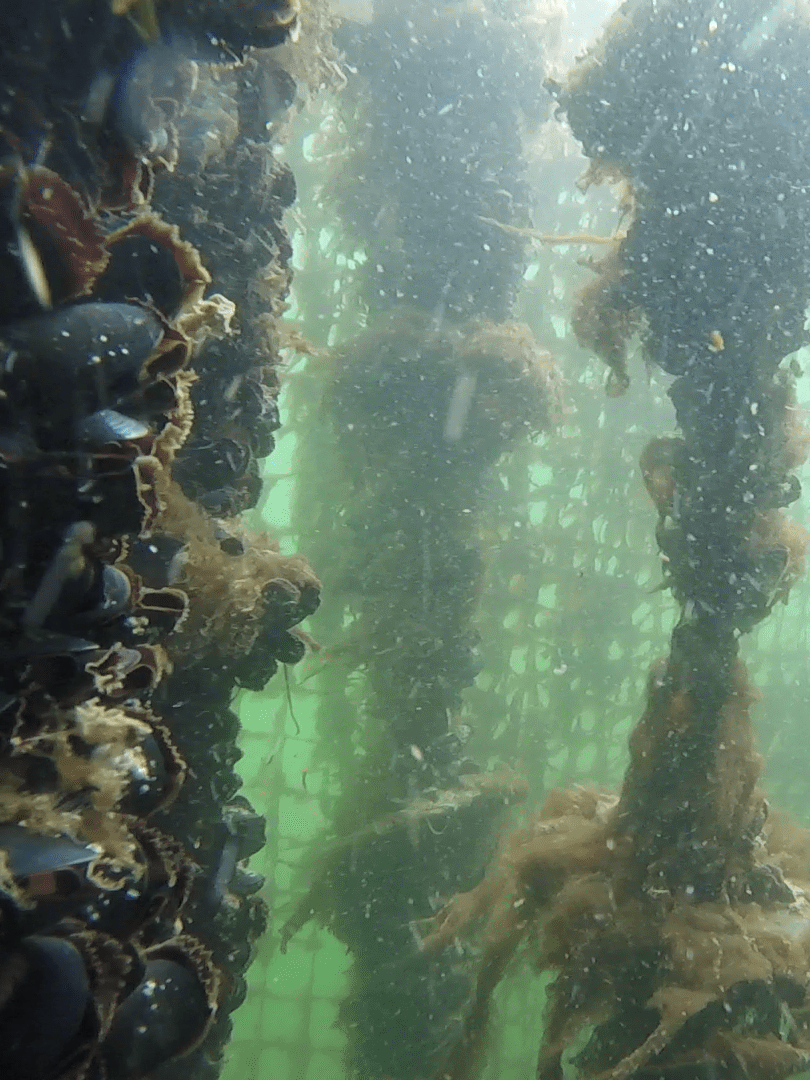

As a grad student I was interested in the amount of energy that organisms invest in different processes, including the cost of investing in mechanical strength. Having strong mechanical materials is necessary for animals to stay put in a wave-swept ocean environment. Mussels produce byssal threads to attach to rock, and these threads allow them to remain in place when waves wash over the shore. When byssal threads are weakened or waves are strong, mussels can become dislodged and this can affect their survival. I worked with a group of researchers to evaluate the cost of producing mussel byssal threads. Mussel byssus was cut at a range of frequencies from just once, weekly, and daily over the course of a month-long experiment. We found that mussels whose byssus was severed daily produced more byssal threads to replace the threads that were removed. These mussels also grew less! I used this experiment to evaluate the cost of producing byssus within a Scope for Growth energetic framework (Roberts et al. 2023 Functional Ecology, Blog by student authors).

I am interested in how physical factors and seawater oxygen and pH affect the growth of marine organisms in marine environments. As a graduate student I evaluated the link between seawater conditions and mussel growth and attachment at a field site on Whidbey Island where mussels are grown on mussel aquaculture lines. For this project I partnered with the shellfish farm, Penn Cove Shellfish, and monitored seawater conditions and mussel growth and attachment over time (Roberts and Carrington 2023 Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology)

Lastly, I am interested in how laboratory experiments can inform mechanistic models. Lab experiments can be used to determine the effect of environmental factors on physiology as well as fundamental assumptions of which costly but adaptive traits are prioritized by an organism, and the energetic cost of allocating resources to them. In the summer of 2016 I tested how different temperature and food levels affect mussel growth and attachment in the lab at UW’s marine station at Friday Harbor Laboratories on San Juan Island. I worked with two farmed species, the local Northern Bay Mussel and the Mediterranean Mussel. I found that mussel growth differed depending on temperature and food level, but there was no significant effect of these two factors on byssal thread production, suggesting growth is more sensitive than byssus to these factors and that there may be a fixed cost of byssal thread production regardless of whether there is energetic limitation (Roberts and Carrington 2021 Marine Ecology Progress Series).